By Jonathan Zdziarski

courtesy zdziarski.com

Many governments (including our own, here in the US) would have its citizens believe that privacy is a switch (that is, you either reasonably expect it, or you don’t). This has been demonstrated in many legal tests, and abused in many circumstances ranging from spying on electronic mail, to drones in our airspace monitoring the movements of private citizens. But privacy doesn’t work like a switch – at least it shouldn’t for a country that recognizes that privacy is an inherent right. In fact, privacy, like other components to security, works in layers. While the legal system might have us believe that privacy is switched off the moment we step outside, the intent of our Constitution’s Fourth Amendment (and our basic right, with or without it hard-coded into the Constitution) suggest otherwise; in fact, the Fourth Amendment was designed in part to protect the citizen in public. If our society can be convinced that privacy is a switch, however, then a government can make the case for flipping off that switch in any circumstance they want. Because no-one can ever practice perfect security, it’s easier for a government to simply draw a line at our front door. The right to privacy in public is one that is being very quickly stripped from our society by politicians and lawyers. Our current legal process for dealing with privacy misses one core component which adds dimension to privacy, and that is scope. Scope of privacy is present in many forms of logic that we naturally express as humans. Everything from computer programs to our natural technique for conveying third grade secrets (by cupping our hands over our mouth) demonstrates that we have a natural expectation of scope in privacy.

Layered privacy, or rather scope of privacy, is all about how far reaching one’s expectation of privacy is; better said: to whom is the conversation privileged? For example, having a private conversation with my wife in the bedroom, with the door closed clearly comes with an expectation of privacy. If I have kids in my house, however, and I open the bedroom door, any parent would tell you that I don’t have any expectation of privacy anymore: anything my wife or I say is very likely to be overheard, and possibly even used against us by our own children. At the same time, however, even the government wouldn’t make the argument that simply opening the bedroom door breaks my expectation of privacy to the degree that would justify unwarranted domestic surveillance. If my kids eavesdrop, they’re the ones in trouble. So, even within the confines of our own castle, it’s very obvious to see that privacy has layers: it has scope. If privacy has layers inside our homes, and in our very nature we exercise scope of privacy, then certainly we have (or should have) layered privacy outside of the home. If you doubt layered privacy exists, consider that you can’t even make for a discussion about privacy in this instance without answering a very important question: from whom? The scope of my kids, my neighbors, or the scope of an eavesdropping government?

Scope of privacy follows us outside of the home as well. Most people have the general mindset (whether they realize it or not) that the scope of one’s privacy is typically limited to one’s communications channel within the area, based on their visual assessment. If I am in the middle of the desert, having a quiet conversation with the only other person there, a reasonable scope of privacy for most Americans would be that my conversation will only be heard by the person I am speaking with. Reasonable privacy expectations do not permit for a hidden microphone to be planted in the cactus next to me, a drone flying overhead watching my every move, or other outrageous or covert violations of my privacy that the average person is unable to detect with the naked eye. It sounds outrageous, but put this into a real life scenario, where a man confesses to a victim’s gravestone at an empty cemetery, where law enforcement planted a hidden microphone. Did the man have an expectation of privacy? Clearly, he had some semblance of it (yet the government didn’t think so). The man had a reasonable expectation that only those within earshot (namely, the deceased) would hear him. Our current system of thinking allows for the government to “switch off” one’s expectation of privacy for nearly any reason in public, however this line of thinking is flawed. Whether a person realizes it or not, they’re exercising some form of privacy in public.

Take this one step further; if I am in a park having a private conversation with someone, it is most individuals’ mindset that their privacy will be limited to those people who are within earshot – it is a reasonable expectation that any “leakage” of my privacy will be confined to the immediate “airspace”, based on human hearing. For example, if I see my nosy neighbor come by, I know that my expectation of privacy is diminished because they’ll likely gossip it around. Most people will only allow their voice to carry far enough to reach the intended recipient, in order to create what you could call a “privileged channel” of communication. Audio (or video) enhancement is not within most people’s ability to detect with the naked eye, and therefore they’re unable to assess their surroundings to account for this in choosing the method they use for establishing this privileged channel of communication. Notice I didn’t say “secure” channel here; as humans, we’re flawed and cannot ever create a perfectly secure channel – we can’t even do that with technology half the time. I said “privileged” for a reason; it is an attempt to create a private channel, usually using the only facilities available to a person: speaking softly, based on the surroundings. It is therefore only reasonable that a person having such a conversation would expect privacy only up to the level that their voice can carry as heard by the human ear. If you wanted to compare this to how technology works, this is equivalent to having a private conversation with someone across the Internet, believing that the conversation isn’t susceptible to a man-in-the-middle attack, and is otherwise secure. If you suspected that your conversation would be compromised, you never would have engaged in that conversation to begin with – therefore, the fact that you are even having a conversation is proof that you have an expectation of privacy. This presents a very important concept: privacy and security are two very different things. If someone breaches your security, that doesn’t invalidate your right to privacy.

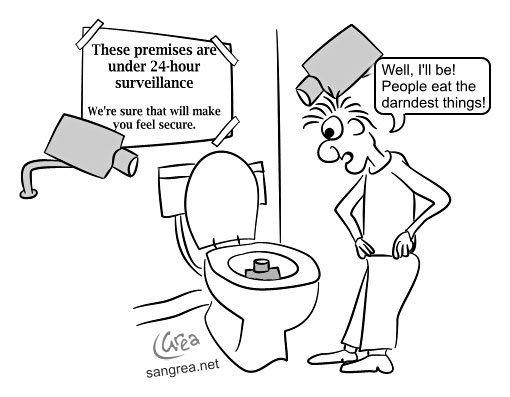

Privacy in pubic is now being destroyed to the point to include any activity you conduct over the Internet, whether it’s been technically designed to be private or not. The IRS has recently come under fire for spying on Americans’ email under the guise that using email surrenders one’s expectation of privacy. Anyone who understands how email works knows that its design intent, when working properly, keeps email private: it partitions off one’s email from any other users on the network, and on the server. It’s inherently private, unless of course a hacker breaks into the system and steals your privacy. Simply because email exists in a public environment doesn’t invalidate one’s expectation of privacy. Consider a single-room bathroom inside a public department store or restaurant. It is surrounded by the public, however our law still protects the inside of those four walls as a private place. Just because a criminal could potentially kick in the door and snap a photo of you on the toilet doesn’t suddenly remove your right to privacy inside this room, yet the same argument is being made against electronic mail and other forms of otherwise private communication.

A reasonable expectation of privacy, as it pertains to human nature, isn’t about geographical space, nor is it about whether the government has the ability to “hack into” your privacy. The government has no right to say that, “because we can spy on you in a public bathroom, you have no right to privacy”. Reasonable expectation of privacy is about intent to have a privileged channel of communication. Simply leaving one’s home does not surrender one’s right to privacy under our Fourth Amendment. Privacy, as it pertains to human nature, is – in its rawest form – based on a desire to have a private conversation. This is exercised in one’s assessment of surroundings, and controlled transmission (e.g. how far your voice travels) in the area, based on realistic expectations assessed visually.

A better legal test for privacy is this: did the individual attempt to create a private, privileged channel of communication with the intended recipient? We already use this test in the digital world. If your computer has a password on it, you’ve established a privileged system and expectation of privacy. It doesn’t matter how strong your password is (just like it shouldn’t matter how strong your ability to keep your conversation from being overheard is); since everything is fallible (even technology), if you attempted to protect your privacy in any way, you should be considered to have an expectation of privacy. In verbal communication, this translates to simply speaking at a level consistent with directed communication. The security of your communication is as irrelevant as the strength of your password. Did the person attempt to have a privileged communication with someone else (regardless of whether they were in public or not)?

It’s not hard to see the can of worms this opens for lawyers, which is precisely why lawyers have attempted to flip our privacy rights on their head, and somehow suggest that we have no right to privacy whatsoever, unless we prove otherwise. But in reality, our right to privacy should be guaranteed unless we take reckless steps to surrender it. Attempting to make the argument that audio or visual enhancements from microphones, cameras, drones, or the like, should compromise this is essentially making the argument that “because the government can spy on you, they have a right to”.

People should be consciously thinking about privacy in terms of layers, instead of allowing the government to do the thinking for them. The landscape has shifted dramatically in today’s world with regards to privacy; this is largely in part the result of politicians, rather than society. When politicians and lawyers begin to control how we as a society view privacy, it can only lead down the road to an inevitable totalitarian government, with a surveillance, nanny state stop on the way. The privacy of American citizens was so cherished, and is so critical to a free country, that the framers of our Constitution made it an exclusive item in our Bill of Rights. No more could we survive as a country without privacy as we could without free speech, or the right to keep and bear arms, to protect ourselves from an overstepping government. Privacy was never meant to be taken for granted, and was never meant to be stripped from Americans.